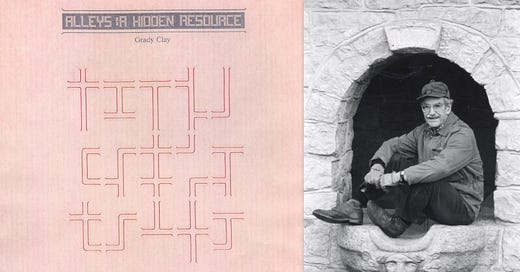

Alleys: A Hidden Resource by Grady Clay

Local writer Robert Kanigel, author of a biography of Jane Jacobs, gifted me this little 1978 volume by Grady Clay (1916-2013), a journalist and urbanist who specialized in landscape architecture and urban planning. Clay is perhaps best known for his 1974 book Close-Up: How to Read the American City, and was perhaps one of the first true urbanists (it seems he pretty much invented the term “urban affairs” while working as a reporter at a local newspaper in his native Louisville, KY). He worked in the same sphere as pioneering observers of urban form and phenomena like Jane Jacobs, Ian McHarg, and William Whyte.

Alleys is a study of the history of alleys in the United States, using Louisville as a case study. In the introduction, Clay outlines how alleys went from being a standard, natural feature of early American cities (essential for infrastructure and services, of course) to falling out of favor around the turn of the century.

Racial and class-related stigma, along with real sanitation concerns, led cities such as Washington, DC to try to limit the form. As land speculation increased in the early 20th century, alleys were done away with in new subdivisions to maximize profit and please the sensibilities of the genteel upper classes. This was the case in some planned garden suburbs like Guilford. As cars replaced horses, stables and carriage houses in alleys became more or less obsolete. This trend continued well into the ‘60s and ‘70s, as the ideologies informing urban renewal regarded as insalubrious and dangerous rather than a necessary form — take for example Harlem Park’s inner-block parks, which replaced alleys and alley houses.

As hinted to in the title, Clay argues that alleys are under-appreciated and that they should be 1) included in new developments and 2) valorized and optimized where they already exist. He was writing this at a time when conversations about ADUs, cottage courts, and alley houses were not already in progress; he was the conversation-starter. But this wasn’t a romantic or sentimental argument — Clay was anticipating the real usefulness and economic benefit of alleys as a potential use for new housing and commercial use that some urbanists later on have observed and transformed into real-life urban policy. I quote here how he summarizes his main arguments:

Alleys that work like streets should dress like streets.

Alleys that serve neighbors should repel strangers.

Alleys facilitate — by accommodating rerouted traffic — that most difficult of all maneuvers, the closing of a street.

Alleys give owners of commercial properties a chance to double their frontages and increase their profit.

In hilly and river-bank cities, alleys enhance the split-level uses of old commercial space.

Vacant alley land also can be put into “cover crops”

Invisibility, which is now a threat to alley use, can be turned to the advantage of alley users.

Cities need close-in sites for many new public structures. Alleys often offer precisely such sites at minimum cost and disruption."

Clay’s Alleys provides a solid theoretical and contextual foundation for modern-day efforts to liven up alleys in Baltimore City — whether that be closing alleys off for private neighborhood use, encouraging the construction of ADUs, permitting retail, or burying power lines. I continue to believe that a pilot project on one to three alleys in Mount Vernon, for example, with collaboration from the City and various private/civic interests, would be a worthwhile exercise — though, admittedly, maybe commercial vacancy should be lower on the main streets before we start thinking about overflowing retail to the alleys. The way to achieve this is to actively encourage developers to come and build more housing, so more people can live and spend their money here.

New hope for Lutherville Station TOD?

On Monday February 4, ULI Baltimore’s TOD Product Council held an event at Lutherville Station, the plot of land that Mark Renbaum has been attempting to develop into a town center for seven years now. Maryland Housing Secretary Jake Day, Delegate Robbyn Lewis, MDOT TOD chief David Zaidain, and Renbaum himself were on hand to talk about how this project has been held up by a Lutherville Neighborhood Association hostile to the idea of any apartments whatsoever and unwilling to compromise. Signs stating “Save Suburbia” — about as close as we can get to an overtly segregationist slogan in the year 2025 — have popped up. This opposition was aided by the Baltimore County Council — which, when Renbaum tried to get the land rezoned from Commercial to Mixed-Use after a lengthy community engagement process, downzoned the land to detached residential (16 units per acre), essentially killing the project. Note how practical land-use decisions are poisoned by political considerations — the fear of being voted out.

Klaus Philipsen began with a data-driven presentation demonstrating how Baltimore County is stagnating due to high housing costs stemming from low production, and a disjointed and unattractive public realm. He laid out the case for why the Lutherville Station TOD project isn’t just something that should be built; it is an absolute necessity for the future economic health of Baltimore County. If TOD can’t be built on this absolutely perfect site with a motivated developer and cooperative public authorities — what the hell are we doing? Lutherville Station is a test of what we’re worth.

Delegate Robbyn Lewis spoke of the importance of in-person organizing, consensus-building, and giving potential opposition a positive vision of what good land-use decisions (i.e. TOD) can look like. However, she did not shy away from expressing her firm convictions that allowing localities to block needed housing is quite simply wrong. She got into politics in the first place after being radicalized by Governor Hogan’s cancellation of the Red Line, which she had done intense community organizing work in support of. It was heartening to see an elected official speaking with so much conviction and controlled anger.

Secretary Day bemoaned our systems around land-use decisions, in which we allow projects to advance to quite developed stages before there is a guarantee that it will actually be built. Neighborhoods are given veto power simply by virtue of being adjacent to the plot of land in question, with no regard to how necessary the project is for the larger public good. He went on record to single out Baltimore County as having a particularly disgusting land-use regime.

The potential lifeline for the Lutherville Station project is a bill, introduced by Governor Moore himself, that would fundamentally shift localities’ legal responsibility in land use decisions. The bill would prohibit localities from blocking needed housing unless they can cite one of six legitimate justifications provided in the bill. Secretary Day noted that this is not a sudden overreach or preemption, because the State of Maryland already has considerable power over local land-use decisions but has voluntarily passed it off to localities. As the negative results of this approach — stagnating housing supply resulting from short-sighted and over-empowered localities — have become clear, the State is clawing back its land-use powers. If passed, this bill might get the Lutherville Station TOD back on track.

Inviting Light Community Kickoff

On Friday night, Yena and I attended the Inviting Light Community Kickoff at the Parkway Theatre on North Avenue. It was half-party, half-unveiling ceremony of the five light-centered public art projects that will pop up (temporarily, I believe) around the Station North neighborhood. Inviting Light follows up on Signal Station North, a sort of preamble focused on data gathering, community walks, and lighting installations focused on public safety.

The projects we saw renderings of last night are decidedly more audacious — garish, even — than what I was expecting based on what I had seen of Signal Station North. I was anticipating more continuity between the two, and that Inviting Light would consist of warm, permanent street lighting infrastructure infused with the conceptual audacity of the artists who designed it. In reality, the five works of Inviting Light are focal points; true destinations.

My favorite, based on the renderings, was the work by Zoe Charlton that will place two large sculptures of female forms, seemingly inspired by the art of either African or early Fertile Crescent civilizations, within the bell towers of North Avenue Market. They will pulse blue light, recalling the presence of the mobile security stations ubiquitous in Baltimore’s more heavily policed neighborhoods — but repurposing it to exude a more holistic, less carceral sense of security (as I understand it) The work will have the presence of sort of lighthouse times two, visible from all angles at the intersection of Howard and North.

This was a short one — thank you for reading.

Its tailor made for an enforcement action by the state Attorney General’s office and its Civil Rights division. (Check out some of the enforcement action by the Massachusetts AG)! The case can be brought in state court as well as federal. Of course, these cases are always stronger with the developer as one of the plaintiffs. Individuals and/or organizations who can allege some kind of injury to their interests can also join as plaintiffs.

Maryland developers rarely, if ever, file Fair Housing Act administrative complaints or lawsuits to challenge policies or legislation that kills or delays their plans for housing development. They should be using this leverage and the Lutherville project —which even has the state behind it — is an especially clear cut case of intentional discrimination and an egregious example of why litigation is a necessary response.