District Trash Containerization

How more density can help solve our garbage problems

My turn-of-the-century apartment building is known among people who pay attention to the everyday management of my neighborhood as a problem building. Every week like clockwork, between Thursday morning and Friday morning, bags of household trash pile up on the curb next to the alley outside of our building. The sidewalk in that area is permanently stained from trash juice.

It’s a scene that is familiar to New Yorkers but seems out of place in Baltimore City. Seeing trash where it shouldn’t be is pretty common throughout the city — some low-income neighborhoods are unfortunately treated like illegal dumping grounds — but Mount Vernon is particularly stricken with trash problems because the majority of its housing stock is comprised of large rowhouses that were converted to walk-up apartments. The result of these conversions, some of which were likely un-permitted, is that any rule to leave aside central indoor space for trash collection was was not enforced. Non-compliant properties seem to have been grandfathered in, given the benefit of the doubt.

The result is a whole district with consistent mid-rise density, but with a systemic lack of indoor garbage storage. This results in tenants keeping trash in their apartments until trash day, when the sidewalks suddenly overflow with municipal wheeled trash cans (or at worst, piles of bags). This has downstream effects like the occasional occurrence in the middle of the week when your trash can has filled up quicker than usual and is getting unbearable, so sheepishly bringing it out to a city trash can in the dead of night is the only option. While single-family homes get city pick-up and large apartment buildings contract out their pick-up, small and medium-size apartments are a gray zone.

Rather than retroactively force individual actors to adopt individual solutions, perhaps it is most efficient to look towards a public, shared solution to address our collective trash problem: containerization.

“Waste containerization refers to the storage and collection of waste from movable bins or stationary containers, rather than bags. Trucks typically have lifting devices, either fully or semi-automatic, to empty the bins or containers, which brings ergonomic benefits to workers.”

from a report by the Center for Zero-Waste Design (linked here)

This is an excellent reminder for those who are leery of density that density is exactly what is needed in order to make a district trash containerization scheme work. The same maxim applies for public services in general. While some may associate increasing density with more trash, more cars, and more problems, density itself doesn’t inherently cause any of those problems; it’s just a matter of good management versus bad management. District trash requires economies of scale in order for the investment to be worth it, and some lower-density neighborhoods must be immediately written off from the district trash list, but could become eligible over time if enough infill housing is added.

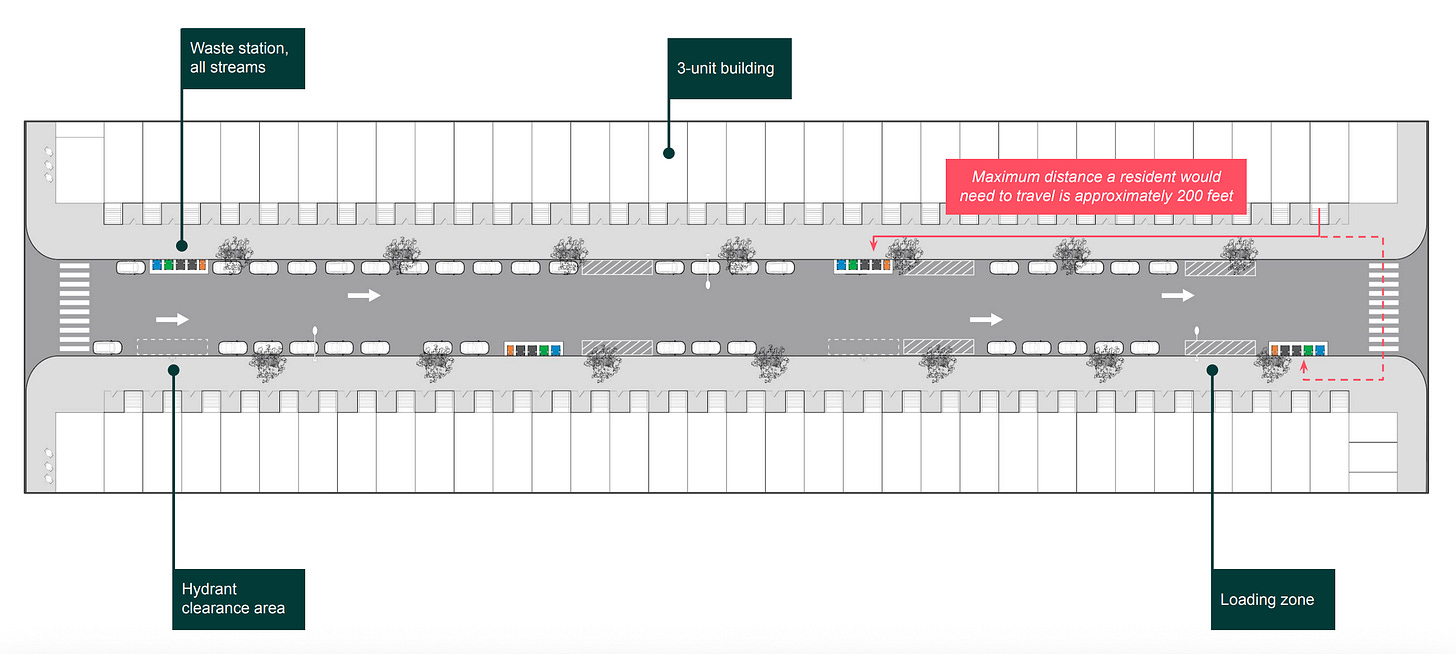

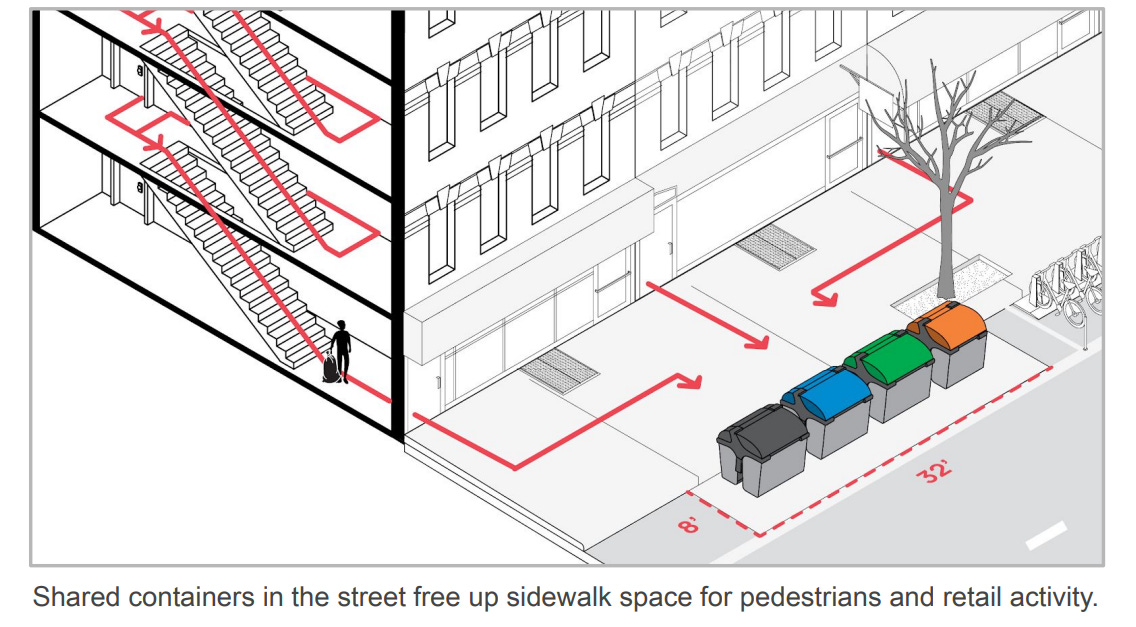

The idea is that while it makes sense for single-family homes to use wheeled trash cans, once you start increasing the number of units for a given property, it makes less and less sense to just keep adding wheeled trash cans, and more and more sense to adopt a more consolidated approach. In practice, this manifests as large containers permanently installed on the street, in line with street parking.

New York City, which has been in the process adopting something approximating this approach for the past decade (though it seems CfZWM feels they could’ve done better), has stalls for large wheeled containers fully above ground. In Europe it is common for for containers to be affixed to the ground or fully underground, with a small, unobtrusive metal receptacle. Some systems have built-in compactors, and the city of Bergen, Norway has even adopted a system with a network of subterranean vacuum tubes. While there are varying tiers of containerization in terms of aesthetics, size, and practicality, even the most basic system is an improvement over cluttering the sidewalk with wheeled bins and loose trash bags.

Some leading benefits of containerization listed in the CfZWD report:

Reduce litter and rats. Keeping trash containerized keeps sidewalks sanitary and pleasant.

Revitalize our streetscapes. Trash slowly eats up sidewalk space, hindering accessibility and making people-centered interventions like outdoor dining less attractive.

Improve worker safety and dignity. In the 21st century we should embrace technology rather than forcing sanitation workers to perform repetitive, arduous motions.

Reach zero waste goals. Programs that tie fees to volume can incentivize waste reduction.

The photo and the video above (video from Geneva, courtesy of John Lansing) give a sense of what this can look like in real life. For sanitation employees it means less stops and easier (though surely skilled) work. For neighborhood residents, it means simplicity, the ability to take out trash at any point in the week, and a liberated streetscape — trash out of sight and out of mind. For developers and landlords, it means less individual responsibility for trash issues — and for local government, it means less time spent chasing after “problem” landlords.

Developing a district containerization program in Baltimore would ideally start as a pilot project. It just so happens that Mount Vernon is one of the few neighborhoods in the city with the amount of residential density that would justify such a program. While the capital investment may seem steep for just one pilot project in one neighborhood (and equity concerns could arise), this pilot would be designed to be replicable for other neighborhoods as soon as their residential density reaches a certain threshold. Extremely dense areas like Harbor East wouldn’t need this because the buildings already contract out their waste hauling. The hope is that neighborhoods like Hampden, Federal Hill, and even Upton will see enough steady equitable growth in the future to justify a district trash program modeled on the original Mount Vernon one.

The pilot would require coordination between DOT (to handle the streetscape design and removal of street parking spaces), DPW (to manage the procurement of new bins and specialized trucks), Planning and DHCD (to clarify requirements for new buildings), and Midtown (the community benefits district that already handles some trash pick-up in the area).

While the details have to be figured out and the money would have to be found, it is clear that the solution to Mount Vernon’s trash problem already exists. By tackling the issue head-on and implementing a containerization pilot program, Mount Vernon could be a model that eventually spreads to other areas of the city.

It also strikes me that while Baltimore has seen a lot of waste-related organizing in the past years — in the form of the Less Waste Better Baltimore Master Plan, the Wheelabrator debate, big plans for compost facilities, the Sisson Street Dump controversy, and an upcoming building deconstruction bill — waste containerization must be brought into the conversation. It’s an intuitive solution to a problem that most people can relate to. As much as we might say that waste is ignored, it really is a salient issue that is on peoples’ minds, and an initiative like this could attract a lot of interest and support. Embracing containerization could be a great way to re-center conversations about how sustainability and waste reduction intersect in practical ways with smart, people-centered public space management.

Thank you for reading. Please read the great CfZWM report if you want to learn more! Other references here: