I’m writing this article to build upon and clarify three of my other articles — the ones about Sutton Place, Inner Harbor West, but most of all apartment construction in Baltimore from 1950 to 1968.

In all three articles, I made vague gestures to how the federal government assisted private developers with the construction of multifamily rental housing. The main premise that I had gathered was that if you were a private developer trying to build an apartment building, the federal government would happily provide some kind of guarantee that made it feasible to build. Whether was a construction loan with fixed interest rates, or insurance for the mortgage, I frankly had no idea.

My hypothesis is, first, that through some means, the FHA funded market-rate multi-family construction at impressive scale — and, second, that a majority of the high-rises I list in my article had their mortgages insured by the FHA. We’ll see if this holds up to my research.

Here is how the FHA described itself in the year 1960.

“The Federal Housing Administration operates housing loan insurance programs designed to encourage improvement in housing standards and conditions, to facilitate sound home financing on reasonable terms, and to exert a stabilizing influence in the mortgage market. The FHA makes no loans and does not plan or build housing.”

What jumps out to me here is that the FHA “facilitates sound home financing on reasonable terms,” but “makes no loans.” It plays a mediating role between the private lender and the private borrower by providing mortgage insurance for approved lenders.

Quoting from a 1965 pamphlet on Section 207 (Rental Housing), FHA-insured projects must be “economically sound.” That is to say, they are what we call “market-rate.” Privately owned and operated. They don’t depend on ongoing subsidy to cover rents — instead, the rents will change according to supply and demand. Normal apartment buildings. The pamphlet takes care to remind us that:

Rental units involved in FHA programs are separate and distinct from public housing units and should not be confused with them. The Federal Housing Administration, which operates mortgage insurance programs, and the Public Housing Administration, which operates the public housing, are two completely different Government agencies.

A brief history of the FHA

The federal government’s involvement in the production of housing in the US started in 1934 with the Federal Housing Administration, designed to support the private market during the Great Depression that had begun five years earlier. This came along with a National Housing Act of 1934, which had two main programs. Section 203 insured lenders against losses on single family homes, while Section 207 did the same for mortgages on multi-family rental projects intended for low-income families. Neither 203 nor 207 saw much uptake in the first few years, but Section 207 is what we’ll be focusing on.

Around 1935, the FHA began distributing guidelines to private investors on which neighborhoods were best (and worst) to invest in. These block-by-block guides nearly always fell on racial lines. Private investors didn’t need anyone to prompt them to be discriminatory, but the significance lies in these practices being codified by the government. It was the FHA’s guidelines for rating neighborhoods that HOLC (the Homeowner’s Loan Corporation) used to develop their famous “redlining” maps, which has resulted in HOLC taking the blame for redlining despite the FHA being the true discriminatory actor in the federal government.

In December 1946, President Truman released $1 billion in FHA mortgage insurance, mostly for multifamily rental housing, which really helped get things going — multifamily units insured by he FHA increased from 45,571 during 1940–1944 to 265,213 during 1945–1949.

Two years later, in 1948, Congress passed Title VII of the National Housing Act, which allowed the FHA to guarantee interest rates on mortgages for multifamily rental housing (a mortgage, in this context, being a long-term loan that a developer uses to build a multi-family building). In the words of the FHA in its 1960 annual report, Title VII “authorizes the insurance of a minimum amortization charge and an annual return on outstanding investments in rental housing projects for families of moderate income where no mortgage is involved.”

In 1950 Section 213 added financing for housing cooperatives, and in 1954, provisions for rental housing in urban renewal areas were provided by Sections 220 and 221. FHA insurance was extended for senior housing projects in 1956, and in 1961, to condominium projects. In 1960, extending Section 207 to rental apartments for families without children (one-bedrooms, essentially) was considered, and seemingly adopted at some point. Through these additions, the FHA expanded its ability to act as counter-cyclically and support many sectors of the private housing market. As the authors of a HUD policy brief on the topic write, “from 1934 to 1958, the FHA insured . . . 39.7 percent of all multifamily construction. In the postwar years . . . the agency insured well over 70 percent of the multifamily market.”

What is FHA mortgage insurance?

Let’s zero in on what FHA’s mortgage insurance really means, in plain language. Well, it is clearly helpful because it provides developers access to cheap insurance in the case that they default on their loan, right? But hold on a minute. From what I can tell, it goes beyond just that.

Starting in 1948, as I noted a few paragraphs above, not only was the FHA providing insurance, but it was effectively fixing an interest rate around 5% for mortgages that multifamily developers could depend upon. While the FHA was not the loan-issuing body (that would be some private sponsor), the FHA was providing a layer of security, an extra bump — a guarantee — that made projects feasible to take a risk on. To understand the basics, let’s look at a case study — back to controversy-riddled Sutton Place.

In January 1963, as construction on the building was nearing its end, a controversy emerged. The owner/developers of the building, led by Marvin Gilman, were also acting as the builders, under the name of the Sutton Place Construction Corporation. This was perfectly legal under the rules of the FHA, which had approved a $5,592,000 mortgage loan likely under Section 220, serviced by a private lender — but the FHA made an error, and Gilman took advantage. A sum of $917,000, about one sixth of the total mortgage loan, went directly to the builders, $560,000 of which was the standard amount that the FHA was going to allow the owner to keep as profit for undertaking the construction of the building — but that $357,000 was not accounted for. Gilman tried to pretend it was earmarked for outfitting the restaurant, but the FHA didn’t buy it.

The point of that story is not even to revel in the drama, but to showcase the basic role the FHA played at this time: certifying the mortgage loan, and setting a fixed interest rate for its payment over time as a precondition for certifying it. A 1966 Sun article indicates that the typical high rise financed under Section 207 had an interest rate of 5.25%, plus a 0.5% insurance premium. The FHA was effectively attempting to make everyone happy by lowering the amount the developer had to pay back per month and up front. An FHA-insured loan covering 90% of total project costs clearly caused many developers to bite. All this assistance made it theoretically less likely for the developer to default on their loan — and if they did default, the lender’s investment was insured, which was the core goal of the FHA’s multifamily operation from the beginning.

Indeed, in 1965, the company that held the construction loans and mortgage for Sutton Place pulled out as mortgagor — foreclosed — due to missed interest payments and high vacancies, so the FHA took over the mortgage and paid the lender the unpaid balance it was owed. Without this guarantee, Gilman may not have been able to find a lender in the first place for this risky project. According to the Sun article, the FHA had insured 90% of the construction cost, meaning that the remaining 10% had to be raised by Gilman directly, because the lender wouldn’t lend anything if it wasn’t insured (this is the $560,000 that Gilman had the right to keep as profit).

Sutton Place was likely insured under Section 220 (added in 1954) because it was built in an urban renewal zone, but it’s the same mechanism as Section 207 — maybe just lower interest rates.

Let’s look at data and newspaper articles from the period to get some more texture. The FHA’s 1960 Annual Report defines Section 207 as “authorizing the insurance of mortgages, including construction advances, on rental housing projects of eight or more family units, and on mobile home courts.” Continuing on,

“Section 207 project mortgage insurance in 1960 totaled $269 million and covered over 19,400 dwelling units. Increasing by more than two-fifths over 1959, the Section 207 insurance volume reached a new all-time high for the third consecutive year and for the first time in 5 years exceeded the volume of insurance reported for any other project program . . . By December 31, 1960, total Section 207 insurance had passed the billion-dollar mark ($1,086 million) and represented nearly 14 percent of all FHA multifamily housing mortgage insurance, The bulk, $1,061 million, of this insurance covered the financing of 123,300 newly constructed rental units and of 1 mobile home court containing 200 trailer sites.

So by this time, the FHA was helping the private market pump out over 100,000 units of rental housing per year. In 1959, the FHA revised its rules — increase per-room and per-unit mortgage limits — to allow its services to extend to (and thus encourage) nicer, higher-rent apartments. This seems to have done something — the number of FHA-insured multifamily units rose from 172,946 multi-family mortgages from 1955-59 to 279,350 from 1960-64. By the early ‘60s, there was so much supply of new rental housing that it started causing problems. Nationwide, vacancy rates and defaults on mortgages in FHA-insured buildings started to reach concerning levels and stretched the FHA’s insurance funds thin, as the Baltimore Sun reported in August 1963.

Paraphrasing from The Sun here — looking over the whole national field of FHA-insured rental projects, as of March 15, 1963, a total of 471,416 units had been completed and were available for tenants, of which 60,368 had had their mortgages foreclosed upon — one eighth of the national total of FHA-insured rental projects. Of the foreclosed units, 12,957, or 21.5%, were vacant. This led to an extreme imbalance and deficit in the FHA’s pocketbooks.

That winter an investigation by the US Comptroller General found that FHA practices had “poured millions of dollars into the pockets of private developers.” FHA appraisers had a practice of blatantly overvaluing land, resulting in an average windfall profit of about $78,000 for the developers of the 59 projects studied as part of the investigation. It is this kind of corruption that Nixon was likely thinking of when he gave his reasons for his housing moratorium a decade later — and honestly, this graft may have been a feature, not a bug, of this set of systems that yielded a lot of housing supply. In 1964, another Sun article revealed that the owners of many FHA properties were charging excessive rents and not maintaining acceptable conditions - a direct result of a lack of oversight and inspections from the FHA.

In 1968 the housing element of Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society kicked into full gear. The most well-known housing bill from 1968 is the Fair Housing Act, which prohibited housing discrimination for protected classes — but overlooked was the extremely ambitious Housing and Urban Development Act of April, 1968, which sought to fully deliver on the promise of the 1949 Housing Act to provide a decent home and suitable living environment for every American. Quoting from Fred McGhee’s 2018 article on Shelterforce:

The 1968 housing act included a smorgasbord of housing ideas: Model Cities . . . Section 235 homeownership subsidies, Section 236 rental assistance (which gave us the term “Fair Market Rent”), business insurance, and a robust increase in public housing construction. The act declared that the goal “can be substantially achieved within the next decade by the construction or rehabilitation of 26 million housing units, 6 million of these for low- and moderate-income families.”

LBJ’s bill ushered in a frenetic and exciting era of experimental housing, and made plans and funding for big urban projects like Inner Harbor West possible through the New Communities portion of the bill.

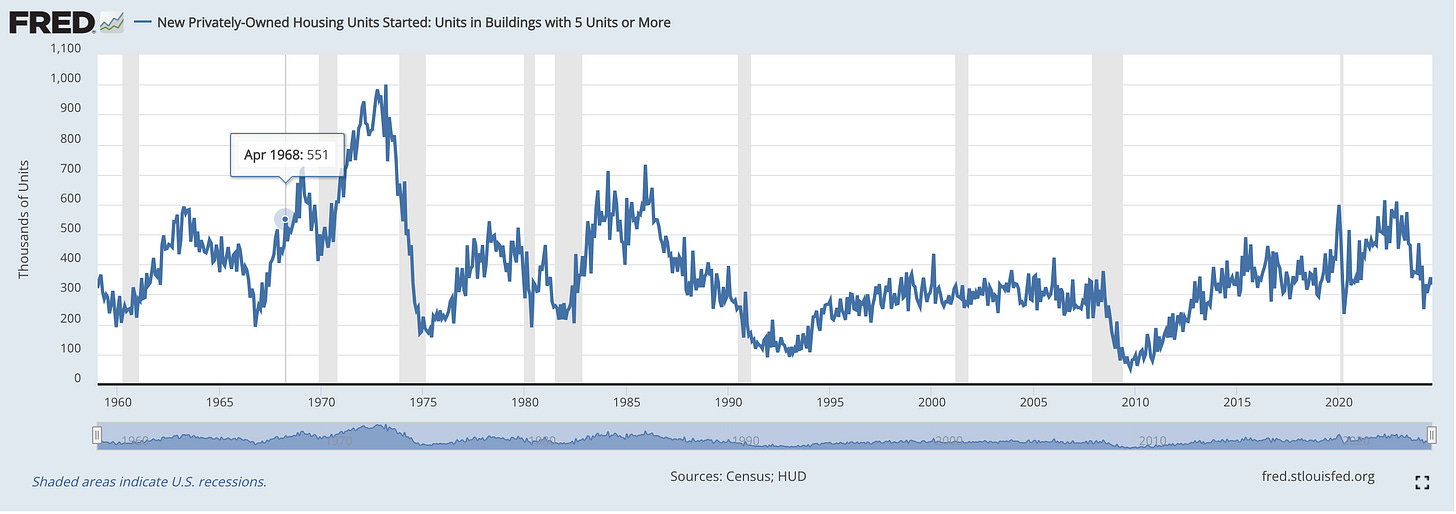

But in early 1973, as we now know, President Nixon issued a moratorium on all federal housing subsidies, citing widespread corruption and inefficiency (this was probably just pretext even if there was truth to his claim). This left projects across the country that had started as a result of LBJ’s 1968 bill dead in the water, and local housing agencies scrambled to mitigate the damage and lost momentum. People who were on the verge of gaining much-needed housing were let down. It is clear that this was a hinge point, and snuffed out very real reforms in federal housing policy that could have led to a very different housing landscape today. All federal housing programs from this point forward were more focused on homeownership, public-private-partnerships, and personal choice (i.e. Section 8 vouchers), rather than directly facilitating the construction of new housing, whether private or public. This was capped off by welfare-reform-adjacent housing reforms during the Clinton administration, including the Faircloth Amendment which capped the construction of new public housing at 1999 levels. If we know nothing else, we know that whatever the FHA was doing for multifamily projects back then, they aren’t doing at the same scale now

What does FHA do today?

How goes the famous Section 207 program, which long allowed the FHA to provide mortgage insurance for new multifamily projects, in the year 2024?

From the HUD website:

Section 207 Program insures mortgage loans to finance the construction or rehabilitation of a broad range of rental housing. Section 207 mortgage insurance, although still authorized, is no longer used for new construction and substantial rehabilitation. It is however, the primary insurance vehicle for the Section 223(f) refinancing program.

Okay. So it’s not even used for new construction anymore. What is 223(f), then?

Section 207/223(f) insures mortgage loans to facilitate the purchase or refinancing of existing multifamily rental housing. These projects may have been financed originally with conventional or FHA insured mortgages. Properties requiring substantial rehabilitation are not eligible for mortgage insurance under this program. HUD requires completion of critical repairs before endorsement of the mortgage and permits the completion of non-critical repairs after the endorsement for mortgage insurance.

Under this section, the FHA will provide insurance on 83.3% of the mortgage for market rate, and up to 90% for deeply affordable projects — but only for multifamily buildings that are already in our housing stock. Surely the FHA has to be helping add some new multifamily projects to our housing supply, though, right?

For this we’ll look at 221(d)(4) - Mortgage Insurance for Rental and Cooperative Housing.

Section 221(d)(4) insures mortgage loans to facilitate the new construction or substantial rehabilitation of multifamily rental or cooperative housing for moderate-income families, elderly, and the handicapped. Single Room Occupancy (SRO) projects may also be insured under this section.

It seems that Section 221(d)(4) most closely resembles what the FHA was doing in the golden age of federal funding for new multifamily housing. But it is clear that this is not currently a vehicle for run-of-the-mill market-rate projects as Section 207 once was — it is reserved for very specific rent-capped projects. In Fiscal Year 2023, the Section 221(d)(4) insured mortgages for 105 projects with 17,222 units — much less than Section 207 at its peak in the ‘50s and ‘60s.

The fact that FHA is essentially penalizing market-rate projects in their mortgage insurance scheme (i.e. incentivizing affordable housing) makes sense in the present context — but it illuminates a huge shift. Half a century ago, the federal government was throwing its whole weight behind subsidizing the production of market-rate multi-family retail units — clearly excessively, at times. Market-rate housing was market-rate in the sense that rent wasn’t capped — but the presence of the word “market” in the term doesn’t mean that its developers were out there facing the economic storms alone, as they largely do now. A lot of market-rate multifamily housing was actually subsidized, just like how our landscape of single-family suburbia was subsidized for white families.

Back then, the infusion of market-rate housing into communities was not protested for reasons of gentrification and affordability in the way it is now, because there were more government resources at the ready to house low-income people (and the government didn’t think twice to do “slum clearance” and then insist people be happy in their new, austere quarters). Today, market-rate housing is protested because, among other reasons, there’s not an equal stream of deeply affordable housing consistently being produced.

The point is not to hold up this period as an ideal time that we must return to. Clearly there were issues, from graft to oversupply. But it is useful to recall the existence that we did things this way for a while — particularly now as the idea of restoring the federal government’s responsibility for funding housing returns to the national conversation.

I find some data

HUD has on their website a database of every terminated FHA multi-family mortgage. When I found this, I naturally clicked on it. It’s a massive excel sheet that starts from the beginning with Colonial Village Apartments in Arlington, VA — the first FHA-insured multifamily project (endorsed in 1935), and and the first “garden apartment” complex of its type in the US. The list continues, mostly starting with the DC suburbs, and then out to other places. I filtered for Baltimore and put all of them into another spreadsheet.

It’s very interesting stuff — the first FHA-insured multifamily project in Baltimore was the Northwood Apartments, on Loch Raven across from the new Northwood Commons shopping Center, endorsed in 1938. Cool!

But what I’m really interested in is all of those elevator apartments that I profiled in that article this past winter. I was hoping that Hopkins House, Gallery Tower, and Dell House — all those market-rate luxury apartments that popped up from 1955 to ‘68 — would show up in my Ctrl+F searches of the FHA database. They did not. Assuming that the database is complete and accurate, the second part of my hypothesis has been proven incorrect.

Among the buildings I profiled in my article, here are the only ones that did show up in this database:

1010 Saint Paul/The Regency - endorsed 1950 - Section 608 Veteran Housing

The Broadview Apartments - endorsed 1950 - Section 608 Veteran Housing

The Marylander - endorsed 1950 - Section 608 Veteran Housing

Sutton Place - endorsed 1962 - Section 220 Urban Renewal Housing

Why are the only three market-rate elevator buildings to show up on the list (other than Sutton Place, which we know about) clustered around the year 1950? And why were they filed under Section 608 Veteran Housing, instead of Section 207 Rental Housing?

Section 608 was not for housing expressly for veterans, but was an emergency program that started in 1941 to jump-start housing supply during World War II and was phased out by 1950. It provided mortgage provisions “somewhat more liberal” (in FHA’s words) than those provided in Section 207, meaning that standards for construction were decreased, and the amount of mortgage insurance allowed per unit was increased. The government, in effect, purposefully opened up loopholes for the private market to exploit. Many of the earlier garden apartment complexes on my map were funded under 608.

A 1954 article in the Harvard Crimson evaluated the 608 program that made the Broadview, Marylander, and Regency possible:

Section 608 had a job to do, and it did it. It was created to build apartment houses quickly and cheaply. Even with the large profits that were made, it is doubtful whether public housing could have done the building at a smaller cost to the taxpayer. No one condones the clear cases of fraud and bribery that did occur in some instances. But by and large, the builders acted, and profited, in accordance with the law . . . Instances of inadequate, matchbox construction do appear, but they are rare. There certainly was no widespread jerry-building reminiscent of the 1920's. On the credit side, FHA established a code of minimum building standards that was uniform for the whole country. But more important, it did what nobody else could do: it got the houses built when they were needed.

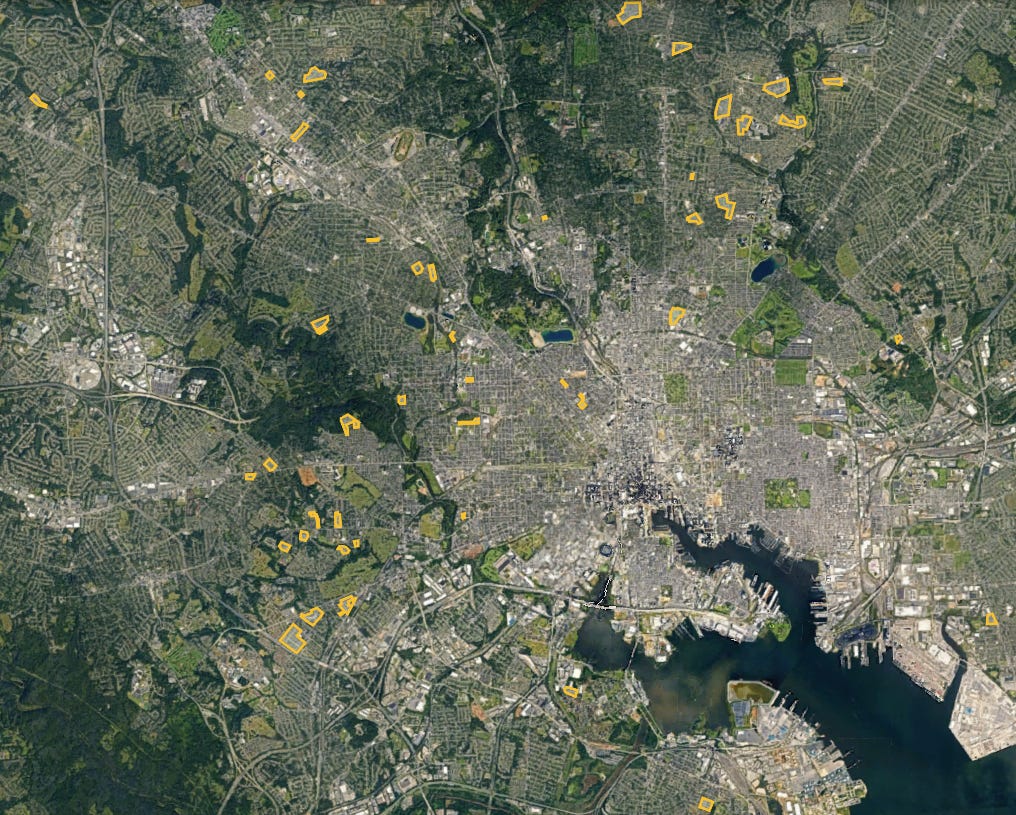

Section 608 also insured many of the earlier garden-style apartment complexes, along with Section 207 ‘Rental Housing’ and ‘Nursing Homes’. I took some time to map all of the garden-style apartments with FHA-insured mortgages in the Baltimore area. These start to stop showing up around 1973, marking Nixon’s moratorium, by which time most of the projects are true rent-subsidized complexes, or towers for the elderly. It’s quite striking just how many of our existing garden apartment complexes were funded by the FHA, and provide decent affordable housing at market rates (and sometimes Section 8, nowadays) for low- to mid-income people to this day.

But back to those high-rises I mention in my article — if terms for FHA buildings under Section 207 were so favorable, why would the builders of Hopkins House, Gallery Tower, and Dell House not have turned to FHA-insured mortgages under Section 207? From everything I’ve read about the FHA’s terms, FHA-insured mortgages would have been hard to refuse. An explanation that comes to mind is that FHA regulations for rents and unit square footage did not accommodate what the developers of those high-rises wanted to build.

Isolating the nationwide database of FHA-insured multifamily mortgages for Section 207 ‘Rental Housing’, plenty (around 600, to be exact) of market-rate towers and complexes come up, all over the country but with many in NY, CA, FL, NJ, MI, and MA. Some examples for texture: Frost House, a rental high-rise in NYC later turned into a co-op to avoid rent control, and 300 Lynn Shore Drive, an apartment in Lynn, MA. The three largest in terms of units are Bell Park Terrace in Queens (1950), River Plaza in Chicago (1975), and Yorkshire Towers in Manhattan (1962).

Somehow, Maryland and Baltimore was largely left out of the Section 207 fun — there are only four in Maryland, and one in Baltimore (Waverley Apartments, not even a high-rise). While my hypothesis about all of those Baltimore high-rises was incorrect, it was not altogether unreasonable given FHA’s intense market-rate high-rise activity in other states.

There will always be questions and uncertainties that will be left unanswered. But I think we got the big picture here.

The terminated mortgages database reveals with certainty just how important the FHA’s multifamily programs were for assisting with the development of garden apartment complexes. Today, these developments represent a good chunk of Baltimore’s naturally-occurring affordable housing, especially on the urban fringe.

It’s worth thinking about how the FHA can better position itself to contribute to a meaningful acceleration in the production of market-rate (and rent-capped) housing. Even when the YIMBYs get all their zoning, permitting, and building-code wins, there remains the problem of how to soften the inherent risks of developing multifamily. Recalling and clarifying the quite mundane reality of the FHA’s services for market-rate multifamily between the ‘40s to the ‘70s is my contribution to the renewed conversation about the federal government’s role in housing production.

Last updated October 2nd.

References

The Baltimore Sun Archives at the Enoch Pratt Free Library

https://www.thecrimson.com/article/1954/4/27/sin-and-section-608-i-pthis/

https://www.huduser.gov/portal/sites/default/files/pdf/Sixteenth-Annual-Report-of-the-Federal-Housing-Administration.pdf

https://www.huduser.gov/portal/sites/default/files/pdf/27TH-ANNUAL-REPORT-FEDERAL-HOUSING-ADMINISTRATION.pdf

https://www.huduser.gov/portal/sites/default/files/pdf/Twentieth-Annual-Report-of-the-Federal-Housing-Administration.pdf

https://www.huduser.gov/portal/sites/default/files/pdf/FHAs-Rental-Housing-Program.pdf

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/HOUST5F

https://www.huduser.gov/portal/periodicals/cityscpe/vol23num1/ch15.pdf

Sorry it cut me off. Was going to say in first years after Fair Housing Act?, HUD under Secretary Romney was actually enforcing non-discrimination --a brief interlude. Otherwise most HUD 207 projects were white-only except Melvin Gardens in Catonsville built for Black occupancy. Lots of detail on multifamily development from 1970 US Civil Righrs Comm'n hearing on Suburban Development in Baltimore. Includes transcripts of testimony of prominent developers, HUD and local officials, etc as well as staff research reports. Keep digging!

Excellent piece! Dont underestimate the liklihood that some of the developers of luxury high rises in Baltimore during this period declined to use HUD 207 mortgage insurance in order to evade "open housing" and rent only to whites. FHA was notorious for financing support to segregated single & muktifamily projects. But in tht four hil George Romney was HUD Secretary, HUD was enforcing the Fair This history of muktifamily development