A One-Way Street to Hell

Why are there so many one-way arterial pairs in Baltimore? Blame Henry Barnes.

Realizing that something exists because someone made it happen in the past is a necessary step in gaining agency and taking action.

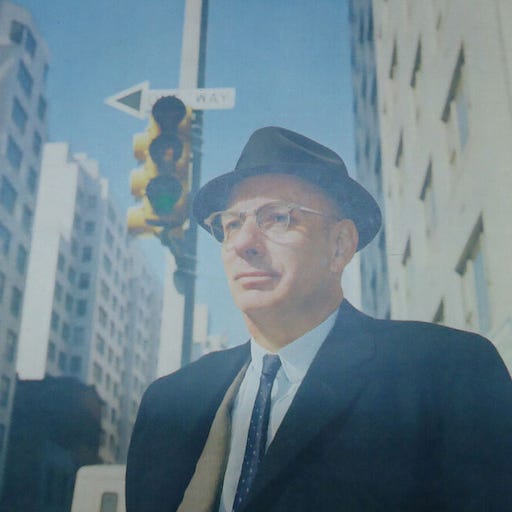

Henry Barnes’ arrival and stint in Baltimore as Director of Traffic, and later Transit & Traffic Commissioner, is a good example of this. His nine-year term was wacky and hallucinatory in many ways, but he left his mark on the city in ways that every Baltimorean experiences every day. In 1953, when Barnes first arrived, the Harbor Tunnel and the Beltway didn’t yet exist; Baltimore was a known traffic bottleneck on the east coast. Barnes started as a consultant, hired to complete a traffic study for Mayor Thomas D’Alesandro. As Barnes recalls in his autobiography, the Mayor called at 5 a.m. the morning after he had submitted his bluntly-worded report and told him, “I just read your goddam report and I think it’s wonderful.”

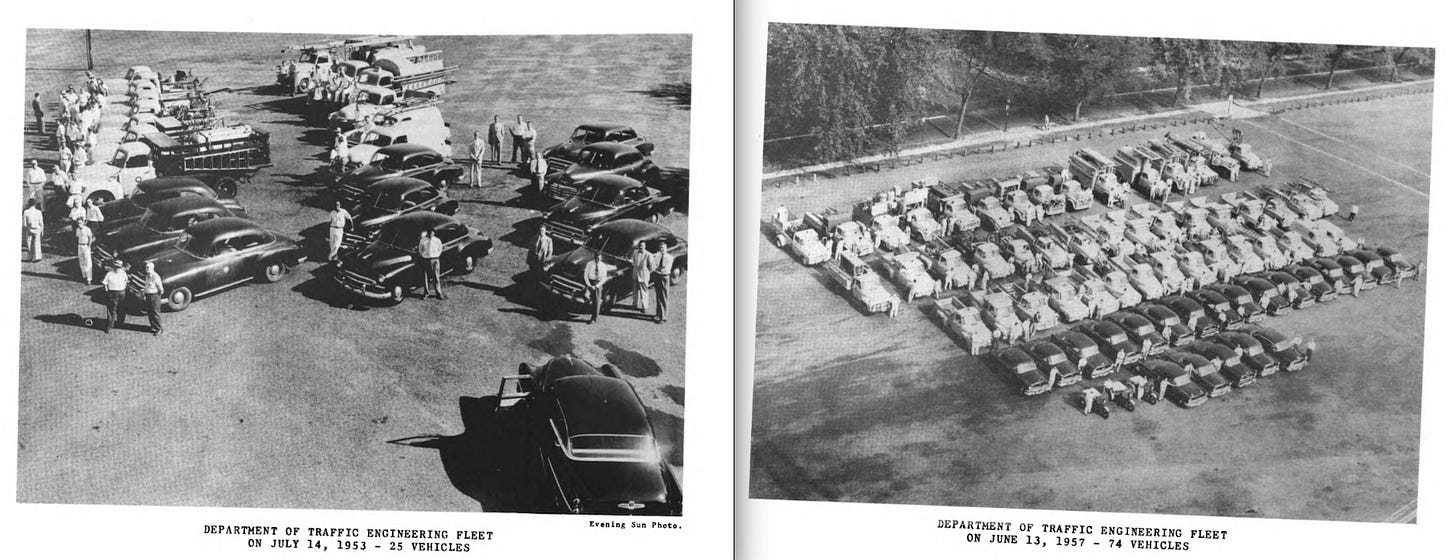

Barnes was instantly hired as traffic director and emboldened by the free rein the Mayor gave him. The Department of Traffic Engineering was formed the same year. Though my authorial voice will be tinted with disdain for this man, I hope I make it clear the extent to which he was impressive as an administrator, a modernizer, and as a mover of people. In these early days of traffic engineering, men like Barnes were held in high regard, almost as miracle workers. Barnes revolutionized Baltimore’s roads and remade the city in his image. We may not like him, but his name should be better-known here.

In 1953, The Man with Red and Green Eyes immediately set about trying to untangle Baltimore’s traffic, which was bad by any objective measure but had settled into a kind of organized chaos that locals lived with and had learned to negotiate. At an early public meeting, as he described, “one female citizen came dripping in mink and exuding all the old airs of historic Baltimore … ‘you just don’t understand, Mr. Barnes … you’re a newcomer here. We have traditions in Baltimore.”

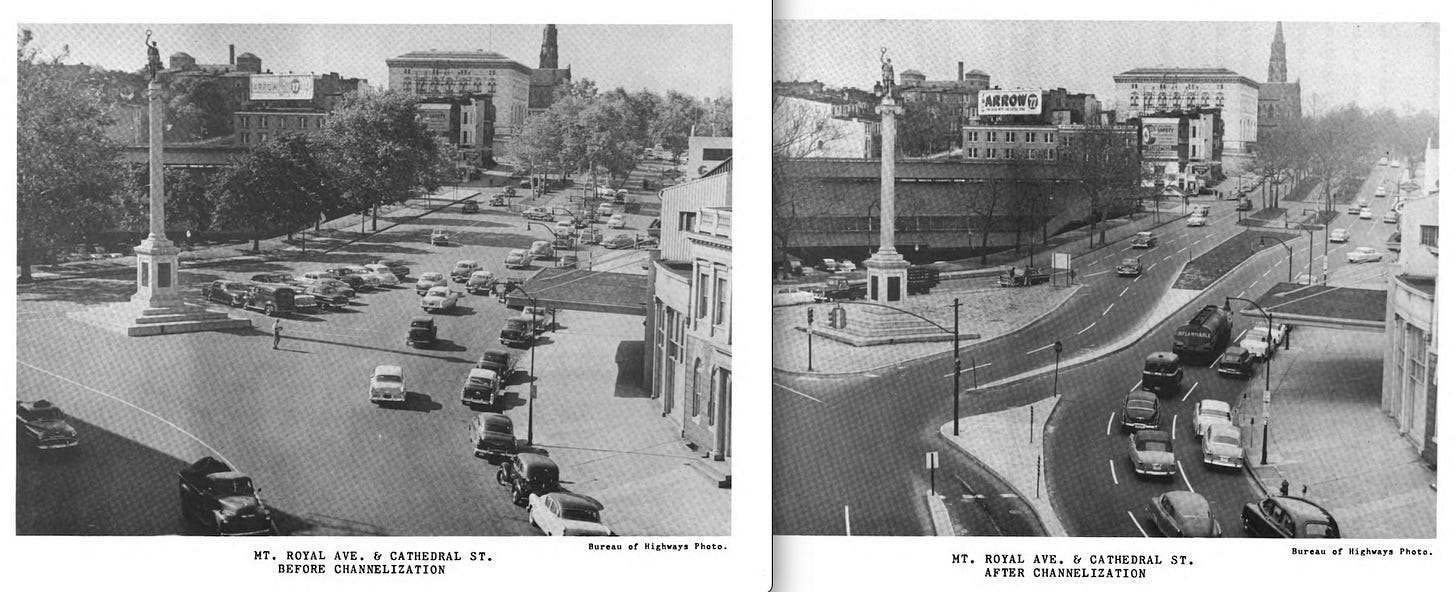

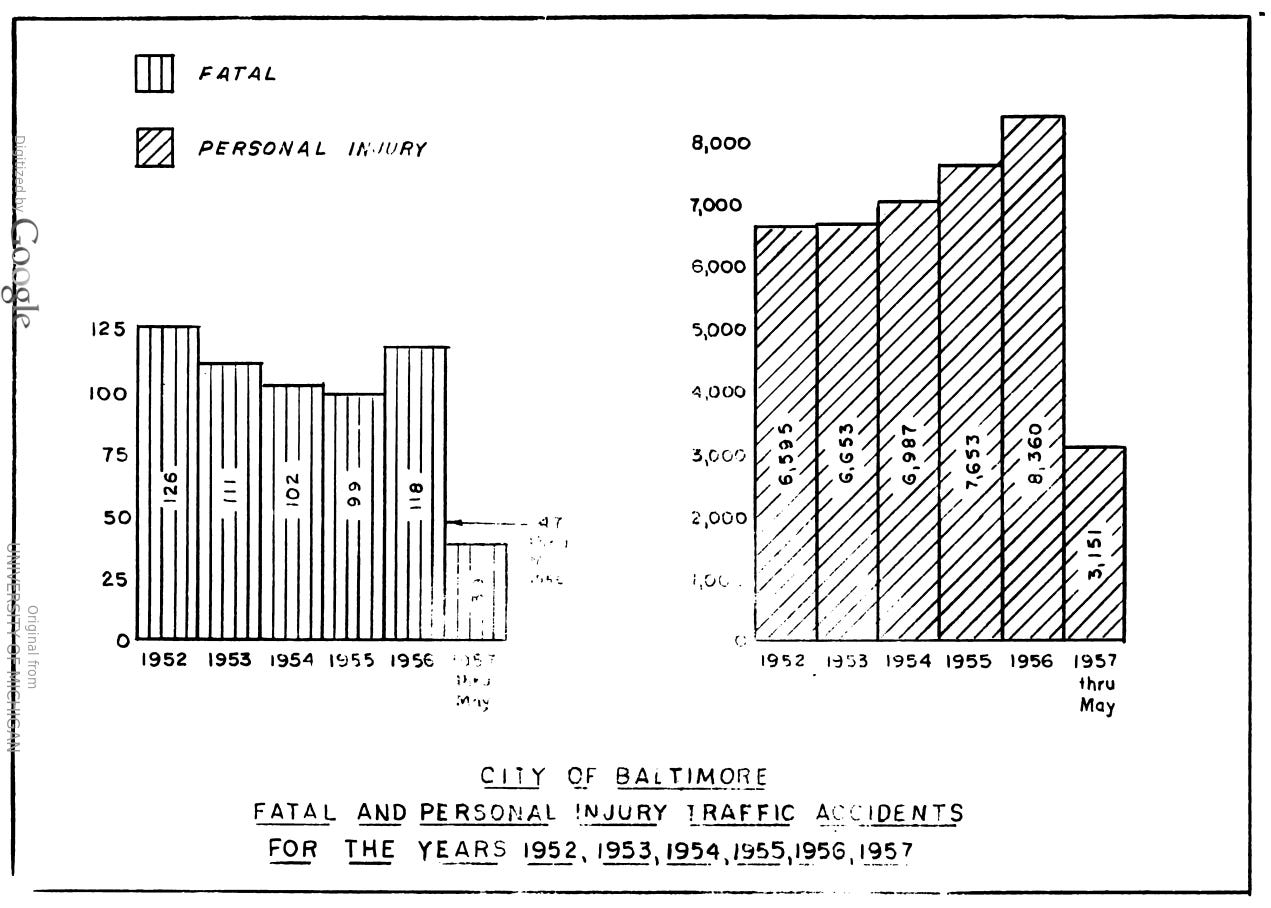

The Monumental City’s many monuments got on his nerves. He ordered the removal the Johns Hopkins Memorial, which, in accordance with Baltimore tradition, had caused several deaths at its location in the middle of Charles Street, near 33rd. The one-way conversion of Calvert Street contributed to turning the dignified Battle Memorial into something to breeze past, encased in a new pedestrian park in 1964. His ballooning municipal army put up hundreds of new traffic lights, thousands of new signs, and painted thousands of new crosswalks and nearly 2,000 miles of road stripes. Subscribing to a planning movement now known as Rational Planning, he used a computer to model traffic in city streets and made changes accordingly. By around 1960, he had implemented computers to synchronize traffic lights (which worked well until it didn’t). Efforts to get this right continue to this day. Most of his real-life interventions were more low-tech, though. He gave his special treatment to hundreds of intersections across the city, and empty oil drums, yellow paint, and rounding corners, now known as slip-lanes, were some of his favorite tools.

When women were driving in cars, Barnes didn’t trust them — “I love them all, but when a woman puts out her hand, you never know whether she is feeling to see if the window is open, drying her nail polish, or making a turn”. When women were pedestrians, he thought of them as frivolous. He threatened to put an end to the Mount Vernon Flower Mart, which he called “a nuisance, a menace, and a pox”, unless the Women’s Civic League could collect an incredible 200,000 signatures in support of the festival. The signatures they collected well surpassed that.

His implementation of thousands of parking meters has probably aged the best out of any of his initiatives, as more recent research has clarified the sound logic and benefits of dynamically pricing the externalities that storing private property in public space creates. Barnes went too far by banning parking on many arterial streets during rush hour, resulting in an added travel lane and making life difficult for locals — these signs are still visible across the city. He was also known for the “Barnes Dance,” the practice of timing lights at busy intersections to stop cars in all directions so that pedestrians could cross freely, even diagonally. This was implemented at a few intersections around Lexington Market, and call back to a lost time when there was so much downtown foot traffic that it had to be planned for.

Barnes’ term as Traffic-Transit Commissioner coincided with the death of streetcars in Baltimore, and this is just as much causation as correlation. The oft-repeated GM streetcar conspiracy claims that car companies colluded to put municipal streetcar systems out of business to sell more buses and cars — but the reality is much more banal. The streetcar tracks were expensive to maintain, and Baltimore’s streetcars ran, well, on the street … and mixed with traffic. This was counter to Barnes’ principles of free-flowing traffic and the separation of modes, and Barnes was a powerful man. It was becoming clear that streetcars would have to bow out in favor of buses and personal automobiles, and it was Barnes who oversaw many of these conversions. In his 1957 report to the Mayor, recounting the accomplishments of his first four years, he noted that, for instance, in 1954, the numbers 13, 14, and 35 streetcar lines were converted to bus operation, and the number 4 service was combined into number 15. During early planning stages of the Charles Center and Civic Center urban renewal projects, Henry Barnes was quoted in The Sun as saying that the project’s success was dependent on the conversion of remaining downtown streetcar lines to buses. This isn’t a question of pointing a finger and revealing some kind of scandalous, unjust story. The times were changing, and Barnes was the man in office to execute these changes. Barnes didn’t lack agency; he played large role in changing the times — but he didn’t do it single-handedly; he was part of a larger ongoing movement spurred by post-war political economy. Baltimore streetcar nostalgia is fun, but spending time stopped at red lights on the light rail is enough to break the reverie. Do I wish Henry Barnes never came to Baltimore? Well, that’s too big of a question. What if I was never born as a result, or something like that? I like my life just the way it is.

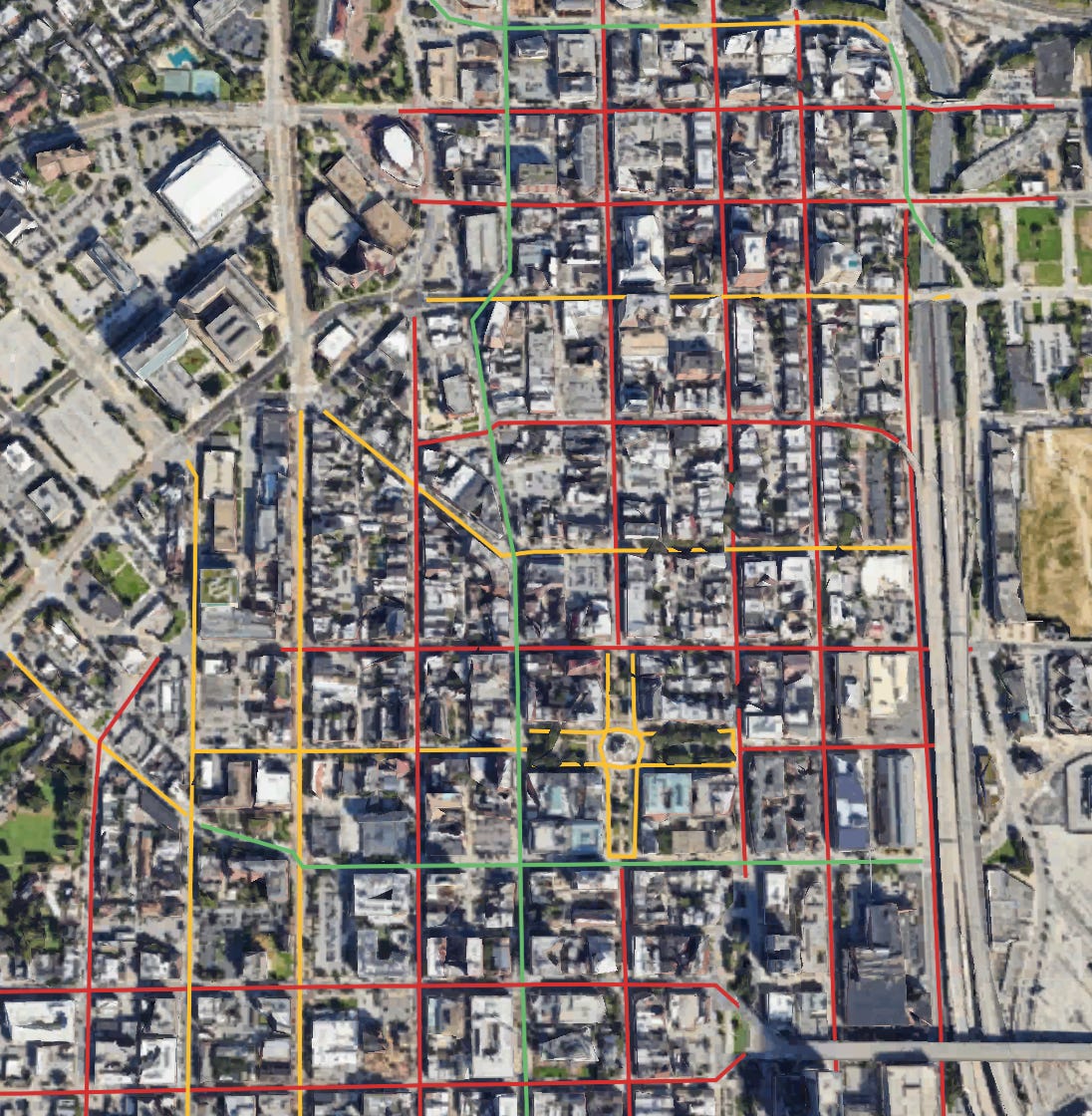

But his worst crime, one that should never be forgiven, was his promulgation of one-way arterial streets. Almost any one-way arterial of two travel lanes or more (i.e. Charles, Calvert, St. Paul Eutaw, Madison, Eager, Pratt, and Lombard) can be attributed to Barnes. These formerly two-way streets may have been congested, but that congestion slowed down traffic and contributed to a robust street life. Drivers had more occasions to slow down and stop in response to parallel parkers, and it was difficult to reach dangerous speeds. When Charles was converted, it was a a bustling retail corridor — and its decline in economic vitality and subjective vibrancy has been attributed to its transformation into an arterial.

Take the Mount Vernon-Belvedere area as an idea example of the adverse impact of Barnes’ monstrosities on local vibrancy. The north-south arterials of Charles, Saint Paul, Calvert, Guilford, and Park shuttle cars to and from downtown at alarming speeds. From east to west, Preston, Biddle, Eager, Madison, Franklin, and Mulberry destroy the quaint, historic feel of Mount Vernon. There’s hardly a normal, two-way street to be found. The correct streets for the Mount Vernon context are slow-moving, well-designed streets with bike infrastructure and no more than one travel lane going each way.

Its important to tell the story of Henry Barnes and his massive influence on Baltimore because it reminds us that if these changes were implemented once, they can be reversed. Of course, Barnes was operating in a completely different level of state capacity — the city’s population hadn’t even started declining, so tax revenue was still strong, and he was completely unbeholden by responsibilities to racial equality (to put it lightly). The extent to which he built up the Department of Traffic Engineering and implemented sweeping changes is truly striking. Our present DOT clearly does not have the budget or capacity to implement large-scale streetscape changes. Instead they must operate in an ad-hoc manner, responding to 311 requests and planning capital investments for many years in the future. Barnes devastated Baltimore City — but if there is something we can carry over from him, it is that it’s fine to be bold in our effort to reverse the damage of mid-century traffic engineering.

Just like how drivers adjusted to Barnes’ bold schemes and striping jobs, people will adjust to, for example, converting Calvert and Saint Paul to two-ways, or one-lane one-ways with back-angle-in parking and bike lanes.1 There’s no need to pretend that blocking a project to appease a few loud voices is noble or admirable, nor that spending money on countless environmental and traffic studies is necessary. Making cities livable starts with streets, and in the year 2024, real cities — yes I said it, real cities — act nimbly, unapologetically, and in the spirit of experimentation. A bit like Hank Barnes.

References

https://web.archive.org/web/20060221041235/http://www.citypaper.com/news/story.asp?id=2431

https://communityarchitectdaily.blogspot.com/2016/04/baltimore-traffic-management-frozen-in.html

https://www.baltimoresun.com/1997/04/12/at-least-he-made-the-traffic-move/

https://www.baltimoresun.com/1997/06/08/baltimores-traffic-was-unsnarled-innovator-henry-barnes-knew-the-effectiveness-of-lots-of-hard-work-and-yellow-paint/

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015078098038&seq=56

In 2014, the DOT commissioned a traffic study to consider converting Calvert and St Paul to two-ways, but after a drawn-out community input process, the change did not go through.